In essence, the story is this:

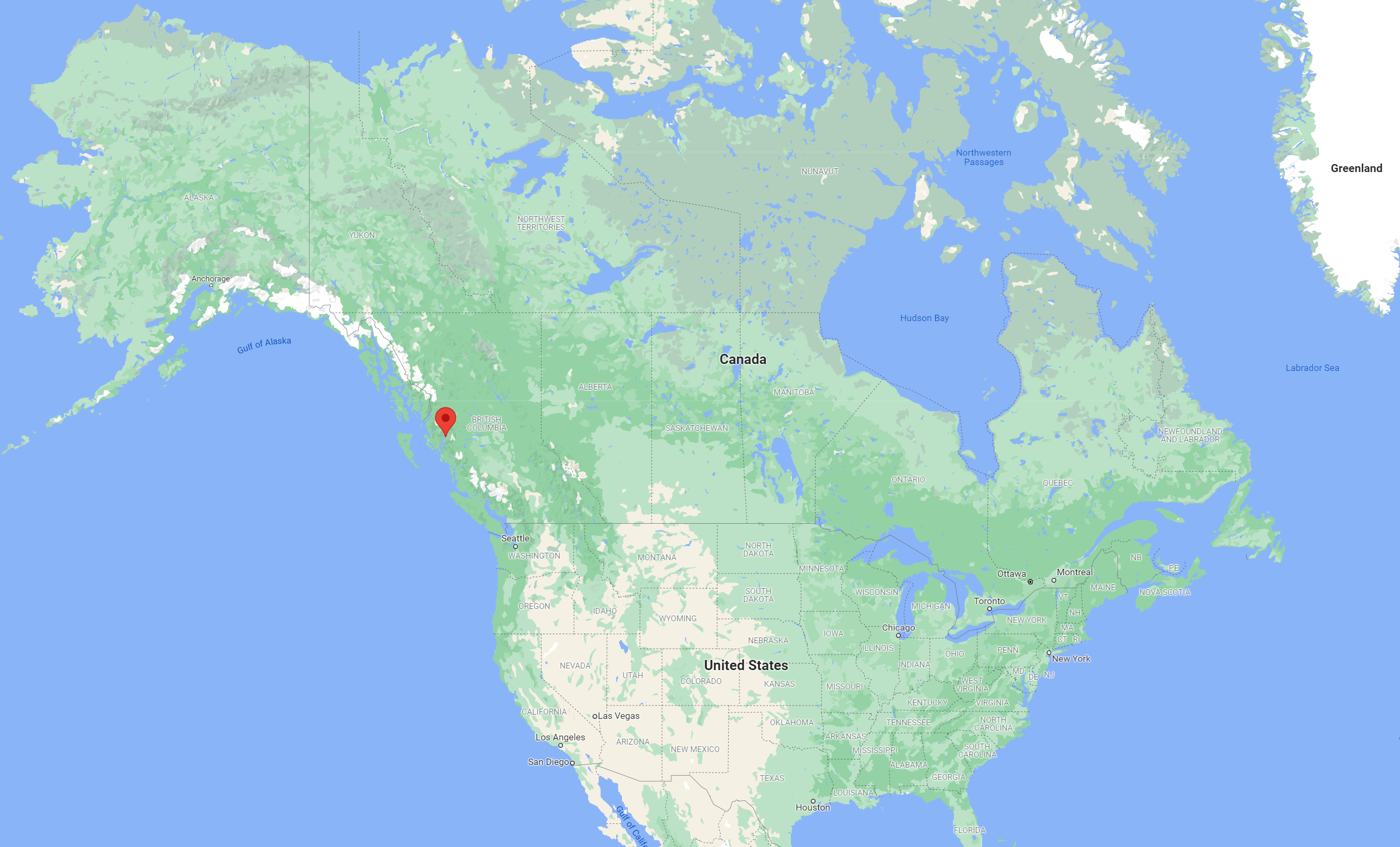

Wa’xaid, also called Cecil Paul, was born around 1930 (his exact birth date is not known) on the banks of the Kitlope River in northwestern British Columbia, Canada. Here he happily played out his first few years before being seized in the residential school swoop that destroyed so many First Nations people. Cecil emerged from that system as a broken young man, and fell into decades of drunken despair. It was a path all too familiar to Aboriginal people of his generation.

So far, so bad.

But somehow the fog that enveloped Cecil lifted a little, and he had a vision of his grandmother, long dead, and from her, he heard these questions: Who are you? Who are you really? Why are you here? What are you for?

Cecil resolved to give up drinking and return to his community in Kitamaat to become a positive force in a very broken village. One day, out fishing in the Kitlope, he came across surveyor’s tape on the banks of the river that marked the valley for logging.

Cecil knew that this was the last part of Haisla territory untouched by industry, and although it might mean jobs and money for his impoverished community, something inside told him that logging the Kitlope would destroy the ecological and spiritual foundations of the Haisla people.

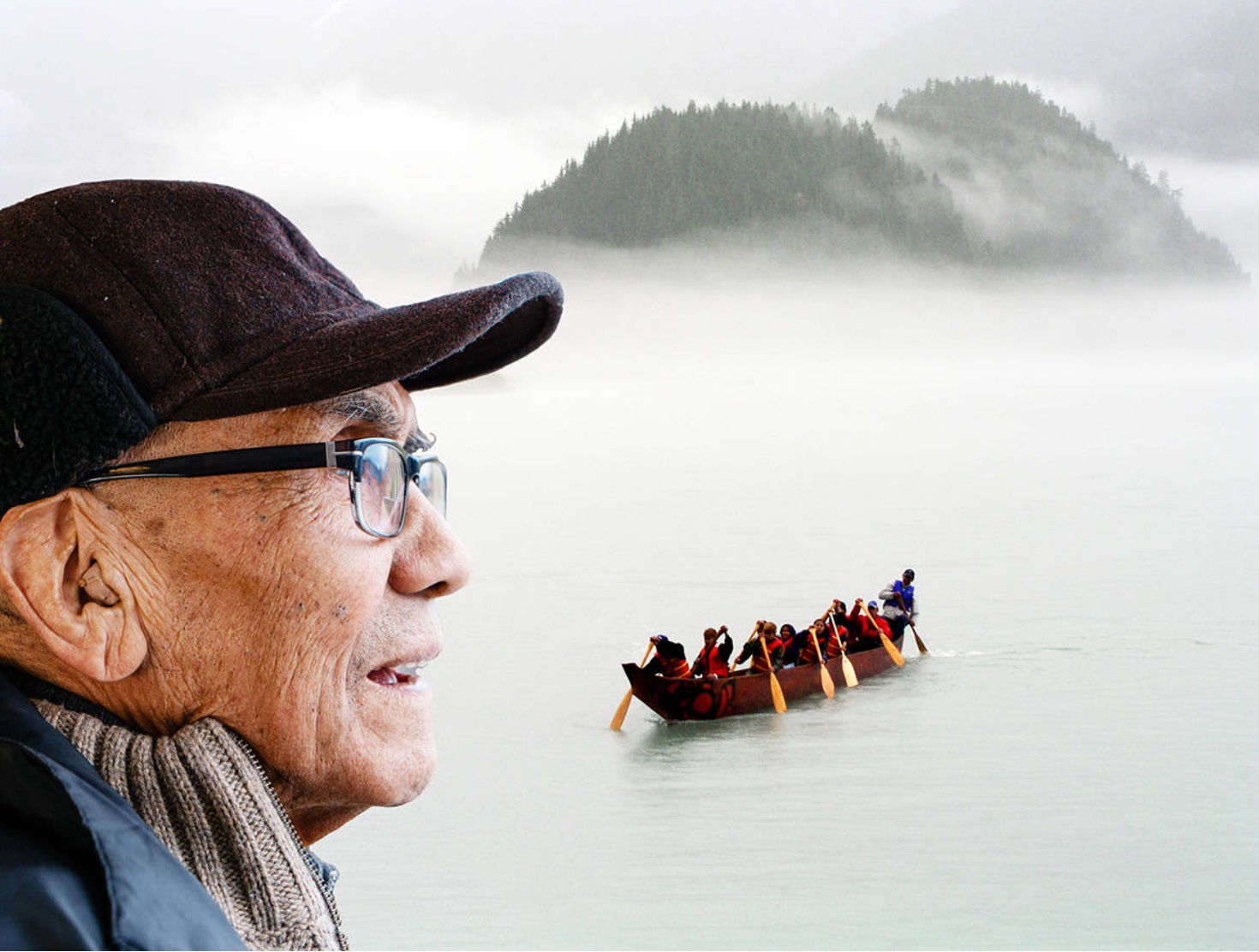

Thus began a lonely journey to convince his community they should spurn offers of jobs and quick money and instead build their recovery as a nation on the protection, not the destruction, of the Kitlope.

“I was alone in a canoe,” he has said. “But it was a magic canoe. It was magic because it could make room for everyone who wanted to come on board, to come in and paddle together. The currents against us were very strong. But I believed we could reach our destination. And that we had to for our survival.”

To cut a very long story short, [all the right people gradually came on board in the magic canoe, and] in 1994 the Kitlope was protected. West Fraser Timber Company voluntarily surrendered its right to log the area, and the Harcourt government of the day designated the Kitlope as a protected area. Today, it appears on government maps as the Kitlope Heritage Conservancy.

But to the Haisla, it is so much more than that, which is why Cecil’s story has become a container of meaning that so profoundly transcends the standard narrative of environment vs. industry or good vs. evil which continues to impoverish and misguide our approach to development world-wide.

To the Haisla, what happened in the 1990s was only incidentally the “saving” of old-growth forests from logging. What really got protected in the Kitlope were the Haisla’s stories.

“You know, you guys call it ‘the Kitlope,‘” Cecil says. “But in our language we call it ‘Huchsduwachsdu Nuyem Jees.’ That means ‘the land of milky blue waters and the sacred stories contained in this place.’ You think it’s a victory because we saved the land. But what we really saved is our heritage — our stories which are embedded in this place and which couldn’t survive without it, and which contain all our wisdom for living.”

Wa’xaid, Cecil Paul, died in 2020, 90 years old.

– By Ian Gill, TheTyee.ca